Dustin Thomas goes from playing the Cabooze to headlining festivals in Bali

May 14, 2013

While most indie bands in the Twin Cities approach touring from a van-centric mindset—you can bring your music anywhere, as long as you make enough to cover the gas money—singer-songwriter Dustin Thomas has followed a completely different path. The Augsburg College grad left Minneapolis a few years ago to try working and busking in Hawaii, and from there has joined forces with the band Medicine for the People to tour Australia and Indonesia.

Even more unique is the fact that Thomas doesn't have a single album to his name. Rather, he approaches music as a performance artist, and his obvious passion for his craft and positive energy has continued to open doors for him abroad.

I managed to pin Thomas down for a few moments while he was in town last month, shortly after selling out a gig at the Cabooze and just a few days before he left the Cities once again to perform at a jazz festival in Russia.

Local Current: How would you describe your music?

Dustin Thomas: There’s kind of three fronts. In Minneapolis, I play with a drummer and bassist, and we really geek out on just playing really loud and playing fun rhythms. I’d say that’s an indie rock vibe, but with an island feel, and more Latin. And then when I travel solo, the main thing I do is like a beatbox, slap acoustic guitar, verse-chorus-verse R&B style love songs and war songs. And then internationally, and in Hawaii, it’s more of gospel, celebratory, nursery-rhyme songs. It’s really inclusive, 30 words a song tops, and just gets everyone in. Last time I played we played one song for 45 minutes, and at that point it’s not even a song anymore. It’s like music class, or a tent revival or something, where everyone has a turn.

The dudes I play with there are like Afro Moses, people who have been leading songs for the last few decades. This guy Afro Moses sat me down and had a talk with me, and he was like, you know, your roots—having dreadlocks, and being African-American—your roots are in singing, for your tribe to sing. And he was giving me this whole down low. And he’s straight from Ghana, he’s played at the Olympics, he’s been singing with hundreds of thousands of people, and he’s like, 'This is what life is. Close your eyes. That’s what it is. Your cells singing make you. Our singing makes the world.'

Do you have any records out?

No. I’m definitely a performance artist. And I’ve recorded so much music. I recorded two songs—one’s like a super goofy electronic Latin song, and one R&B song, but I’ll listen to it later and be like, ugh. At this point, I make my living, and I travel the world, and I don’t have an album. So I might as well do it right when I do it. I don’t want to mess around. Basically, whatever my last recorded live show was, I’ll make copies of that and hand it out. But yeah. It’s funny what word of mouth can do for you. People are like, ok, I’ll take a chance on that.

It seems like bands get wrapped up in feeling like they need to have a new album out in order to tour.

Right? Yeah. Definitely glad to be free of that. And it would be nice to have music I could give to people, to be like, ‘I’m proud of this.’ Or, ‘This sounds like me.’ But I don’t know. I’ve gotta get to that point, and I don’t know where it’s going to be. Do I want to make an album like Frank Ocean or the Weeknd? Or do I want to do a Lumineers/Mumford thing? What do I wanna do? And then I listen to Portage and I’m like, ah, I just want to do it myself. Portage is my favorite band.

For the past year you’ve been touring all over the world. Take me back to the beginning—how did you start traveling with your music?

I would just take any opportunity that would come up, you know. And sometimes it would be like, ok, go to Colorado, to this little diner. And then I’d go play the diner, and some guy’d be like oh, you should open up for me, and it’d be at the Fox Theater or something. So I just started going and—I remember, I think it was in like 2009, we got a showcase at SXSW. And we went and we got a bunch of tips, and we got like three other things down there. One person knows another person and it’s this crazy little game. I didn’t have a CD out, and I went all the way to Australia and Bali. It just got to that point. It’s just taking every opportunity.

Had you traveled outside the U.S. before?

Never. No. So I went to Australia and I was like, woah! And I showed up to Bali and was like, what? It was so crazy. [laughs]

How did you meet people that could help you do that?

I’ve been touring with this band Medicine for the People for like a year and a half now. Those guys are from Hawaii. So I moved out to Hawaii in 2008, and then came back here in 2010, and then went right back out in 2011. It’s hard to stay now, it’s so cold and gray.

Are you from Minnesota originally?

I’m from Missouri, but I went to middle school, high school, and went to Augsburg here. I wasn’t even into trying to tour or do music—I didn’t even take people like that seriously, when I was in college. And then when I moved out to Hawaii I was working this job, and on my breaks I’d just go sit and play guitar. And I’d make more money busking than I would at my job, and I was like, dang! And then I just came back here and I was like, well, I don’t want to work, I just want to play music.

Do you feel like most people have that mentality—that music is supposed to be a side project, and that it’s taking a big risk to try to make it your career?

Yeah, I think there’s awful norms about what being a musician is. And because of that, I think it changes how people get into music. I just feel like a lot of people just talk about gigs, or talk about shows, or ‘I only play this show in this market,’ and do all this stuff. In any business, or any aspect of life, I feel like whatever space you create is what opens up. If you go in with a whack mentality, like ‘I need to work so hard to make this work,’ ‘I need to make sure I’m getting paid like this or I’ll get screwed over,’ and ‘I need to make sure I’m playing only these certain amount of weeks apart, and I need to hit these regions’ ... Well, if you want to approach it like that, you can. But then there’s other bands that just play all the time, and people always come because it’s an experience, and not a spectacle.

In Hawaii we play every weekend, and everyone comes out, because it’s like that. I feel like a lot of bands could make it that experience. But for me, you know, honestly I had to just bang around in the dark for two years to realize, ‘How do I ask for what I want? And then how do I present my most genuine self?’ It wasn’t until I could do that musically that it really started taking off. Because I feel like the signals were not necessarily connecting. So it’s funny to watch other friends who are in the same place, kind of settling into themselves. And Minneapolis is a really embracing community. There’s this whole spectrum of like reggae, rock, roots, jam bands, to really intricate indie music, or ambient music. And then not to mention the underground hip hop scene. I feel like there’s enough of a niche for everyone to kind of find their own place. Of all the places I could have started playing music, I’m glad I cut my teeth in the Midwest.

Is it hard to break out of that super supportive ecosystem and go on tour, if you can have a community here that embraces you?

In Bali and Australia, because of the type of shows we were playing—I mean, I’ve had some really good tours and stuff, but to go into a place where every show you have, there are a couple hundred people that can’t even get in—it just gave me a real idea of, ok, this is what I would be working for. Now it really matters to me. Honestly, what I’m really working for, and what I’d like to pursue is just to be content, with true friendships and true community and true love. And I think if you are an artist, you have to ask yourself: What’s your goal? Is your mission to travel like crazy? If it is, then don’t sit around. Go travel. Do whatever it takes. That’s what we did. We ate ramen noodles out of a gas station for two years, and then it was awesome. But if you just want to feel comfortable and safe, then do that. And both are honorable. It’s about being true to yourself. If you want a world following, or if you want an international following, or if you want a regional following, whatever you want, it’s just making sure that your model represents that.

I think that Minnesota gives you a good idea of what to look for. You can see other scenes where people are more competitive, and you're like, wow, I’m really glad I have what I have. We have friends from L.A. who come and play with us in Hawaii, and they’re like everyone is so nice here! I think it’s harder to drop your guard than it is to put up your guard.

I wonder about the bands who get to a certain level of popularity locally and then just—

Plateau?

Yeah. There’s no motivation for them to tour, if you can just self-sustain here.

I don’t see why there would be. What is the motivation? It’s like any part of your life—if, in your job, you reach that spot where all your needs are met, what are you going to do? Same for me. I had a house here, and I was touring all over, I was about to move to Colorado, and I went to Hawaii on a six week tour, and ended up there for six months. Because it was everything that I needed. If I had that here, I would have never left here. But there’s types of shows I wanted to play that I couldn’t play here two years ago. And now that I can, it’s like, now I’ll just play a couple shows, and hang out and spend time with my friends.

What’s Bali like?

Oh my god. It’s so funny, because I feel like expectation is everything, right? And I went there, and I was thinking it was going to be this heady environment of sustainability and agriculture and lots of yoga and chill people. And we’re flying over Dem Pusar, and I’m just looking out at this sea of lights, and I had this feeling in my chest like where am I? Please, this is Jakarta right? And we land down and get out and drive—and it’s the first time I’ve ever seen slums, other than like East NY or Detroit. So it was really wild, just driving through.

And then our spot was in this place called Monkey Forest. So I wake up, and I see this stream of, I’m thinking squirrels or something outside our window, and I hear these things on the roof, and I’m looking out, and then this thing comes up to me and I’m just like, 'Chase? Are these monkeys?' And he’s like, 'Yeah, get down here!' So I run downstairs and my friend Chase has this huge stick and he’s fighting off these monkeys that are flying at him. They’re just attacking him like crazy. And for two weeks straight it was like that: wake up in the morning and fend off the monkeys. There’s this giant monkey temple where all the tourists go, and the locals teach the monkeys to steal sh*t, and then they throw the monkey fruit, the monkeys drop the iPhone, and then they get $50 and the tourists are like, ‘Oh thank you so much! Oh my god!’ And then on the other side is where all the monkeys sleep. And our house was in the middle. So there’s like 500 monkeys making an exodus from the temple to where they live every day.

Like the monkeys were commuting to work?

Yeah, they were commuting to work. And they’re totally a team. So it’s funny, you know. There’s 2 million people on motorcycles, no filters on the emissions, so you’re exhaling smoke. And you have packs of wild dogs in the street that mob, and geckos, and cain spiders. So for me I basically stepped in and was in fear, I was so scared. And I was like, am I really here for the next seven weeks? It was a lot for me. I was really emotional. Like, holy smokes, this is a whole new place. I’m super scared, I’m trying to be brave; I’m playing this empowering music and I’m scared.

Ultimately, it was life changing. The Balinese people—they are so artistic, they’re so talented. Their entire day is filled with—they acknowledge the rice field, they acknowledge the rain, they acknowledge the tourism, they acknowledge dirt bikes, they acknowledge Vishnu, they acknowledge Hanuman. From the minute to the maximum. And so because of that, I just feel like they are in on this cosmic joke. They’re in on this balance, of how there’s the profound and the profane. They make this ornate offering every morning with sacred tea leaves and woven hand baskets—every day, multiple times—and then they throw a cigarette in there, and a piece of candy, next to the sacred flower and the sacred flower and the rice. It’s the balance. Nothing gets left out. And because of that, I just feel like they’re ready to look at things the right way. Like the guy who is fixing your motorbike or the guy who is your driver, or who delivers your coconuts, he’s probably also a master woodworker or a master painter.

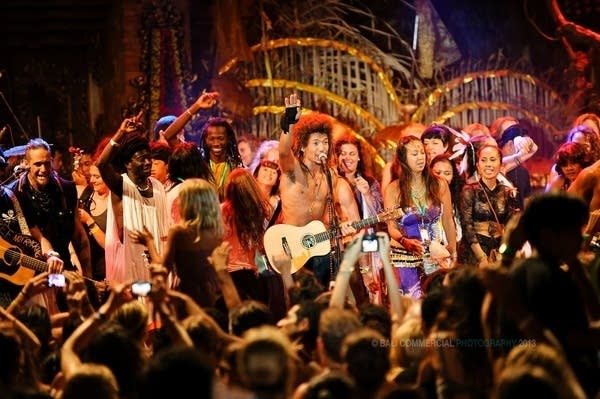

I see everyone in America frowning. They’re just walking around with a chip on their shoulder. And these people are camping on garbage, washing themselves in sewage, and taking all the money they have to just make little offerings. It’s like, ahh! Break me like that. And I totally was. I’m just so blessed because the music out there is so participatory and so intense, and people just want to be involved, so it’s just like this high. To be on stage with 50 people, hanging out, and a thousand people out there, singing along. It was incredible.

Do you think you’ll go back?

Absolutely. As soon as October, and as late as next year for the festival again. The cool thing about Bali is, the way the international community is there—you basically go from one night, I’m staying in a thatched roof with a bunk bed leaning up against the wall, checking out the cane spiders, and then the next night we’re having moonshine, riding past a stegosaurus statue in a villa. It’s just from absurd poverty to—who has a stegosaurus bone in their house? Who does that? How do you get that in Indonesia? So it was such a huge span.

Follow more of Dustin Thomas's adventures and stay up-to-date on his hometown shows on his Facebook page.