Fathom Lane and batteryboy talk vinyl, nostalgia, and songwriting ahead of their dual release show

November 22, 2013

By now we've all heard plenty about the vinyl resurgence, and how the sale of vinyl albums have skyrocketed past CD sales in recent years despite the challenges plaguing the music industry. And we've seen this play out on the local level as well, with vinyl manufacturer Noiseland Industries continuing to press more and more LPs.

But for my money, the easiest way to assess the rise in vinyl albums is to scan the weekly gig lists here in town, where there always seem to be at least one or two shows billed as "vinyl-release parties." This week, two rising singer-songwriter driven acts, Fathom Lane and batteryboy, are even teaming up to celebrate two separate new releases coming out on wax at the same show.

For the younger generation of music fans, vinyl holds a mystical power over our shared musical experiences and nostalgia; you can touch it, you can get lost in the artwork, and you can travel back to childhood with memories of dancing in front of the turntable or finding that first band that was singing directly to you. In a time when we're constantly being bombarded with new music, vinyl offers an excuse to hold still and listen to just one thing, all the way through.

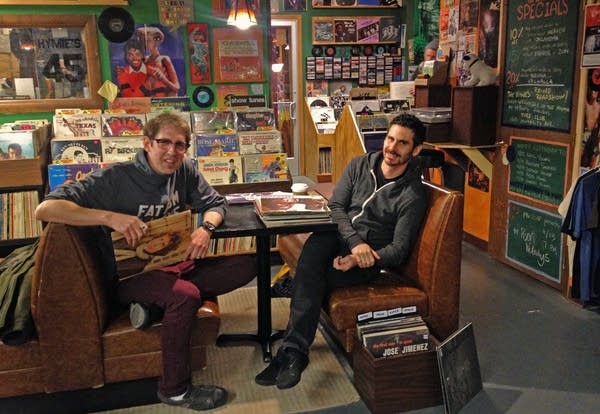

These are just some of the things that I talked about recently with Fathom Lane's Michael Ferrier and batteryboy's Cobey Rouse, the chief songwriters and frontmen of their respective projects. To dive into our shared thoughts on all things vinyl, we met up—where else?—among the stacks at Hymie's Vintage Records and let the conversation wander as each musician picked out LPs from their personal collections to play.

Local Current: Hey guys! Show and tell time. What'd you bring?

[Michael Ferrier holds up Roxy Music's Country Life (NSFW)]

Ferrier: This is dangerous. As a kid, when I got this, I had to hide it. With compact discs or downloads—they don't feel as dangerous. The resurgence of vinyl is so great, because the process of making it is so much more of an art. It has so much more impact, and since the artwork is big, it can have that danger to it. Whereas, now, I mean the music can be dangerous, but before it was the whole package that felt cohesive, as an artistic statement.

Cobey Rouse: It surrounded the music in an experience. Even a cassette did, and vinyl totally did. You get a digital download or even a CD now, and you just put it in, and you listen to it, and you might listen to this song and that one, and you might listen to nothing else. But these [holds up a stack of records], you take it, you put it on, you open it up, you look at it, you hopefully read the lyrics, and you experience the music and everything around it while you listen to it. And it's so different. Digital downloads are almost throwaway; very forgettable, very fast.

Ferrier: We have to figure out how to give music that impact for people again. It did feel dangerous, and it did make a thud when it showed up. [drops album on table] And the fact that it's a pain in the butt to jump around tracks is kind of a blessing, because you're forced to sit there and play it.

Rouse: You lay your tracks in a certain way because you want people to experience it from song one to song whatever, and you don't get that experience anymore. If you put a CD in, most people probably put it in a computer now and shuffle it.

Ferrier: And listen through laptop speakers.

Rouse: I know, and don't you get sad?

Ferrier: Yeah.

Rouse: Even if you put out a video, it's like, I hope somebody plugs this into a stereo or something, because it's going to sound like crap and this is their only experience with us, on YouTube.

Ferrier: And I'm not mixing for laptop speakers.

Rouse: You aren't? I should write this down.

And there's music playing overhead and actual people to talk to; it's way more personal.

Ferrier: I remember going to Northern Lights when it was downtown, they would be playing the craziest music, and I finally got the guts to go up and ask, once. And I think it was Love and Rockets at the time. But I always would try to hang out there for a while, because they usually cycled through different things. That's where I found out about Roxy Music. So, yeah, I mean just being in a record store and letting the folks who work there spin the good stuff is fun too.

So Michael, I know you said your first record was the Beach Boys. What was yours, Cobey, do you remember?

Rouse: Mambo Mickey Mouse. It was a Mickey Mouse Clubhouse record.

Ferrier: Ok, so I would have to revise mine then. I probably had a Pooh record or something. What was your first music record?

Rouse: I know my last 45 was "Living on a Prayer." I was probably about 8 or 9 when I started listening to actual music, and cassettes were big, and 8-track. My parents had an 8-track; my parents didn't have vinyl. We had Captain and Tenille and all that stuff on 8-track. And my brother, who's four years older, had cassettes, and that's when I discovered more. I was enamored with U2 for about seven years. All I did was listen to U2 as a kid.

Ferrier: I can definitely hear that in your stuff. I can hear that—some of the emotional content of the first couple records? I can definitely hear that coming out in your music. So it's definitely imprinted on you. It's funny, when you start trying to trace back to where certain influences come from—

Rouse: That's why these are in here. [pulls up U2's Joshua Tree] I mean, this thing pretty much defined me. Boom. I wanted to be Bono—I think I still do.

Let's play it.

["Where the Streets Have No Name" comes on]

Rouse: I was doing math. I was sitting at my desk doing math, and this came on the radio and I was like, holy sh*t. What is that? And this is the '80s. This was 1987. I define everything in my life by 1987. So I know when things happen based on 1987.

Ferrier: '87 was a big one for me, too. That was Jesus and Mary Chain, Fascination Street by the Cure came out that year I believe, and Pixies' Doolittle. I was working at a record store in '87, I was working at Disc and Tape Masters in Fargo/Moorhead. We would play Oranges and Lemons every day.

Rouse: My only sadness about our album is that we didn't record to tape. And I think I would do that next time. Because we recorded, and then my guy, my label best friend from college, was like, let's do vinyl! And I was like, yeah, I want to, totally, but we didn't record for vinyl.

Ferrier: Did that present any challenges when you to the vinyl step?

Rouse: Not terrible. We mastered it to vinyl. I think our sound kind of lends itself to it, so it kind of fit the format, but we think it would have been a different experience to take it on methodically and plot what we were doing for that experience. But at the same time maybe only 5 percent of your fanbase is going to experience that, so I try to think about that.

Ferrier: The reason my band came together was to make vinyl.

Rouse: Really? That’s awesome.

Ferrier: I’d always had a dream; I would beg, borrow or steal to get records, and I always wanted to make my own record. And making CDs was fun, but it just didn’t seem the same. Even our album cover, I wanted our album cover this time to have it so you could sit down with it for a while and wonder about it. What’s going on with it? So I really sought that out.

[Michael puts on a Hamilton Bohannon record]

Ferrier: Listen to this. What does it sound like? I hope the Talking Heads are sending this dude checks. I think in some of their liner notes they say, ‘Our apologies to Hamilton Bohannon.’ I mean, you hear this chicken scratching—this is the seminal early Talking Heads, what they did, crossed with disco. It's the best party music.

I have a non-vinyl question for you both. You each have such distinctive singing voices; when did you first find your voice, and learn you could sing in that way?

Rouse: You want the honest answer on that? Two years ago, honestly, is when I found this voice. I used to be in an alternative band, and I started singing when I was 13, but I don't think I ever sang well when I was a teenager, and even into my 20s when I had my own band. I always tried to go too high, and too loud. When this project started and I started singing, I found my voice—a lower, more natural voice.

What shifted for you?

Rouse: All of these songs started coming out, and that's the way they were. I started writing a lot of deeply personal stuff, and things I saw in other people that were deeply personal to them—it all just came out the way it's supposed to.

Ferrier: For me, it kind of relates similarly to Cobey—when I wasn't trying to sing for anybody else, that's when I found my best voice. Because I don't have a very professional voice or anything, it's a nasally tenor, and I don't sing with a lot of vibrato, I just try to keep it very simple. But I guess I get in touch with something there; I must be getting in touch with what's happening in the song. I do try to keep it as simple as possible.

For me and my music, that works best, and it also allows for a much stronger singer to be in the band, Ashleigh [Still], and she can hang her stuff on this framework that I lay down. I've just noticed I sing a lot differently when I'm really embodying the song and thinking about the song, and it's really harder to do when you're on stage than it is in the studio. And I do think the studio can be and should be the best representation of what you sound like as a band. That's your chance to say, hey, given every perfect variable, this is what we sound like.

Rouse: I totally disagree. It's my most hated place to be. I can't stand it.

Ferrier: Being in the studio?

Rouse: Yeah. I'm so different when I'm live. I look down, I have my eyes closed, it's like there's no one there, and I'm playing drums with my feet and I'm strumming my guitar and it's this thing, it just comes out. And when I'm sitting there and Peter's staring at me and I have my headphones on, I just get so nervous. I freeze up. I can't stand it.

That's interesting that it's so different for the two of you.

Rouse: It's weird for me, too, because the stage is where I'm the most comfortable, but I'm also quite shy. I will never win one of those lists for Best Stage Presence. I'll be on the bottom. I look down and close my eyes; if I do look up and I do see something, it just takes me right off my train of thought. I used to play looking the other way.

Ferrier: That's very Miles Davis.

Rouse: Yeah.

Ferrier: Jesus and Mary Chain, that's how they came out. They played for 25 minutes and played with their heads in their amps. It was an intense show. So you come from a good long line of people who turn their back on the audience.

Rouse: [laughs]

Ferrier: Do you want to spin another record?

[Cobey puts on Leonard Cohen's Songs of Leonard Cohen]

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otJY2HvW3Bw

Another non-vinyl question: Both of your records feature guy-girl vocal harmonies, and I was wondering if that was a conscious choice, to have a female voice complementing you? And how did you find your musical partners?

Ferrier: For me, I didn't know it was what I wanted until it happened. I had these songs first, and then I started doing the recording process, and we were actually a ways into it when I found Ashleigh. I found her on Facebook; I heard some of her tunes and was blown away. So we sat down, and we sang 'I Hope You Never,' the Tom Petty tune, that was the first tune we ever sang together, and it was just like, 'Oh my god. This is totally different now.' It completely switched my thinking about the entire band. It definitely gelled the idea.

Rouse: For me, I had been playing for about a year on my own, and I was literally starting to feel like a freakshow; this guy who plays guitar, and I'm playing drums with my feet. It was weird. I'm a very up-and-down artist, I suppose. One bad experience gets me down and I'm like, ok, I'm done. I quit.

Ferrier: I've been there. I've had to talk Cobey off the ledge a couple times.

Rouse: So I played in Duluth at a festival in July, a year and a half ago, and my family was there, and about three other people. And I was like, you know, I'm done. This is just ridiculous. I had one more show on the docket, and I went to play that little thing. And I had become Facebook friends with Shannon a few months earlier, and she posted that she was looking to play more shows. So I was like, ok, I'll try it. And she's like, 'Yeah! I remember you. That'd be fun.' And—I'm extremely emotional—I started crying. Like, someone from Cloud Cult actually wants to make music with me. This will be interesting, and maybe I can do something with this!

Ferrier: Awesome, man. That's great.

Rouse: I was thinking violin, that's all. I always wanted to have strings in my music. And the first time we practiced, she started singing with some of the stuff and playing with it, and it was just like, whoo. Same exact thing—I mean, we're oddly parallel, in our paths—it was just like, oh my god, this is how it's supposed to sound.

Ferrier: When you find your catalyst, you really have to embrace it, and nourish it, and ride it out for as long as you can. I'm convinced.

Rouse: It's insane. So we were supposed to do two shows together, and she was digging it enough to stay on for this year. And that was our agreement. She was going to do a year. So now she's moving on, this will be our last show on Saturday, and I'm replacing her with Leah [Ottman, violinist] and Hilary [James, cellist]. And now we have—Eric [Carranza] sings too—so we have four vocal harmonies happening at the same time. And it was like, yeah, that's the way that song is supposed to be, and that's the way this band is supposed to evolve. I just let it happen. It definitely helped—I would describe my voice as raw, and you get that female vocal in there, and yours becomes better.

Ferrier: It's really good to play with bandmates that make everyone else in the band better. And that's what I feel like in this band; we learn from each other, and we're listening to each other all the time.

[Michael puts on David Crosby's If I Could Only Remember My Name]

Ferrier: This album is super underrated. There's a lot of good music from the '70s, but I think this one gets overlooked. Probably because it has several tunes on it that have no words; it's an art record.

Rouse: That's what's always been interesting to me about Sigur Ros—you make a connection with the music, and you have no idea what he's saying.

Ferrier: It's like the Cocteau Twins for me. Yes.

Rouse: That's another thing—when people ask what a song means, very rarely will I say it.

Ferrier: I can usually say something kind of loosey-goosey about it. Like oh, it's about sex, or darkness, or whatever. But nobody gets the full story on what it's about.

Rouse: Everyone has a different reason for falling in love with a song.

Ferrier: That's what a good song is, too; they can map their story onto your song. What I try to do, and hopefully I achieve it, is trying to fill in as few blanks as I can. Because those are the songs I love.

That's such a fine line, because you want to be personal. How do you decide what to leave out, and what to include?

Rouse: I think it becomes as personal as possible when it means that unique thing to that person. Once somebody knows exactly what it's about, then it's my song, not theirs.

Ferrier: That's a good way to put it.

Rouse: Some of my favorite songs—like I never want to know what "With or Without You" is about. I have so many experiences attached to that one song. And then there's ones where you'll hear it, and you're like, oh, that's not what that meant to me. And it destroys your relationship with the song.

Fathom Lane and batteryboy play a dual vinyl-release show this Saturday, November 23, at Icehouse. Find all the details in the Local Gig List.